Aug 11 2020

I recently read the book Make Time by Jake Knapp and John Zeratsky, and thought it was pretty good (3/5).

The book is effectively structured into 4 sections: Highlight, Laser, Energize and Reflect.

This graphic from the book gives a great overview:

From Make Time by Jake Knapp and John Zeratsky.

The book is broken into 4 sections: Highlight, Laser, Reflect and Energize.

For me, the most important section of the book was the Highlight section, and within that, the concept of a Daily Highlight.

The concept is simple: set a Daily Highlight, the one thing that will make your day successful, and prioritize it first and foremost.

This could be a task at work, a personal project, a meeting, exercise, whatever - just make sure it is the top of your priority list.

Make Time has a nice set of tips and tricks to help selecting this Highlight, and how to focus on it, but the gist is pretty simple: nothing else matters unless your Highlight gets done.

I’ve started implementing this at work and seen a notable uptick in productivity throughout the past few weeks.

At first, my thought was there was no single thing that I could attribute as the most important part of my day, and even if there was, there was no way I could have only one. I expected to need 5 highlights, or a Top 10 list to get everything at work done, but I committed and gave it a shot.

What resulted surprised me greatly: most days really only had 1 major thing that needed to get done. If I prioritized that thing, and ruthlessly executed on that one priority, I felt accomplished looking back on my day.

This led to the next level of development: structuring my work around my Daily Highlight.

There are a few things I implemented from the book, but I would recommend buying it (or getting it from the library) if you’re interested as the set of tips and tricks work together into a cohesive system.

The one aspect I do want to focus on, however is my To-Do List.

Setting a Daily Highlight, and some recommendations in the book, pushed me to re-think my method of how I intake information. I want to become an Ask Once person, but my To-Do List system kept falling short.

So I took the advice of the authors and gave this restructuring a try.

Here’s what I came up with.

Daily Highlight

As mentioned above, I set a Daily Highlight. I like to do this first thing in the morning or just before ending my day the night before. Setting this highlight and putting it front and center on the top of my To-Do list reminds me that if I accomplish this one singularly-focused task with surgical precision, I can look back on my day feeling accomplished.

Selecting this Highlight can be challenging, as I often have multiple projects on the go, but the question I ask myself is this:

If I only accomplished one thing to move this project (or myself) forward, what would it be?

This is often easy enough to answer.

Some days it’s a specific meeting that is important. Some days it is crushing through an urgent task or solving a difficult problem. Some days it is going for a run and clearing my head. Nothing says it has to be about work, and it should be, in the words of Tim Ferriss, one thing that eliminates many other things.

It’s the lead domino.

Sometimes it makes sense for me to check my email before setting this highlight, as I can get ambushed by unexpected urgent requirements from our CM overseas or my manager, but more often than not I have an idea of what this is beforehand.

I’ve also found the Hemingway Method to be helpful here by setting that task the night before.

The second part of this is ruthlessly focusing on that task. I will often block out time in my calendar for the Daily Highlight, usually about 2 hours, and do nothing else in that time. I started off trying to set the same time daily, but this proved to be difficult.

So in summary: pick the most important task, make it a Daily Highlight, make it a priority and schedule time accordingly.

The Kitchen To-Do List

The second part of my To-Do list I took from Make Time directly. The authors mentioned how they structure their own To-Do lists, and mentioned the idea of scheduling tasks like cooking a meal: Front Burner, Back Burner, Counter, Kitchen Sink.

I worked in a kitchen throughout high school so I loved the analogy. Cooks have tremendous pressure to be on top of their to-dos in a noisy, fast-paced kitchen, so if it can work for them, it can work for you.

The concept is simple:

Front Burner is the thing that demands your most focused, immediate attention. It probably has some sense of urgency to it. It may not necessarily be the most important thing, but it’s the thing you’re dealing with now. I only let myself have 1 item on the Front Burner at a time.

Back Burner is a set of up to 3 other demands you should keep in mind, like having 3 pots bubbling away on your stove while you tend to the Front Burner. These tend to be tasks you should get done during the day or sometime tomorrow, and are less urgent, but may be just as important. I let myself have up to 3 items on the Back Burner at a time.

Counter is a space for when the Front Burner is overflowing and requires more space. Think of this as your prep station for the dish you are currently cooking. In Make Time they outline this as an area to make sub-To-Dos, for when a project is so big you have to break it into smaller pieces to make progress. You put all those small parts here. I personally don’t find this part very useful, but I like the logic behind it.

Kitchen Sink is where everything else goes. This is the dumping ground, like the dish pit in kitchen. Just throw it there until you have time to deal with it. This is where I intake any new requests on my time, and where the next phase of prioritization happens. All the Front and Back Burner items come from the Kitchen Sink (unless they are literally on-fire urgent). Anything that gets bumped from Front or Back burner gets put in the Kitchen Sink. The Kitchen Sink, thanks to the advances in digital computers, is virtually unlimited. I try not to have more than 30 or so items here, but the whole point is you can have as many as you want. Don’t let the dirty dishes pile too high, but hey, it’s a big dish pit.

This system has been revolutionary for me. Having a structured way to intake information, set a prioritization scheme for myself, and in a glance understand what to focus on, has been a breath of fresh air. My productivity has increased so much, I even have time to write this article.

Other Sections

I’ve also implemented a few other sections to expand on the Kitchen To-Do list:

Personal is where I put personal To-Dos. I thought about having a separate Kitchen To-Do list framework just for personal items, and I may expand to that as this list grows, but for now I like having work and personal items all in the same page. This section has no limit

Waiting On is where I put items that I am waiting on someone else. I often put a sub-bullet-point with the timeline and when I should poke and prod them on getting updates. For example, I am working on some packaging graphics and the next step is for our marketing team to put something together. I’m waiting on them to finalize the graphics and then I will review and send to our packaging vendors. This item “send packaging graphics to vendors - waiting on design from Marketing - Tuesday Aug 18 - poke on Friday” gets put into this category. This section has no limit.

Daily Routines is a set of small tasks (<25 minutes, most <10 min) that I try to do every day. When I do one of these routine tasks, I cross it out. In the evening I uncross all of them. If a task is something I want to drop, I remove it from the routine, and likewise if I want to add something I put it here. I was using a daily habit tracking app but found it quite cumbersome and overwhelming, so having a list of 5 or 6 things I try to do daily is quite helpful as a reminder. This section has a limit of 10 or so, but realistically shouldn’t be more than 5 core things. Any more than that and it’s time to revisit.

The Ultimate To-Do App

I have been using a Chrome extension called Mindful to implement my To-Do list.

I cannot recommend it enough. In simple terms, it makes any new window a simple text interface. It has bullet and number functionality, let’s you tab for indents, and has check-boxes, which I love. I have implemented this entire system into this interface, and any time I need to review my to-do list or add an item, I simple open a new browser window.

This has proven to be the most effective implementation I have ever used.

I’ve given Evernote a try, and I like it - especially that it syncs between my phone and computer - but found the interface cumbersome to use.

I have also used the ol’ pen and paper method, but I find it difficult to keep things structured.

This app has the perfect balance of simple and useful. No BS. No auxiliary features. No interface on-boarding. Just exactly the way you expect it to work, the first time.

I also really love that any time I open a new window to perform a task, the most important things on my to-do list are there staring me in the face. It helps pull me back when I’m procrastinating.

Putting it Together

So here’s how it gets put together.

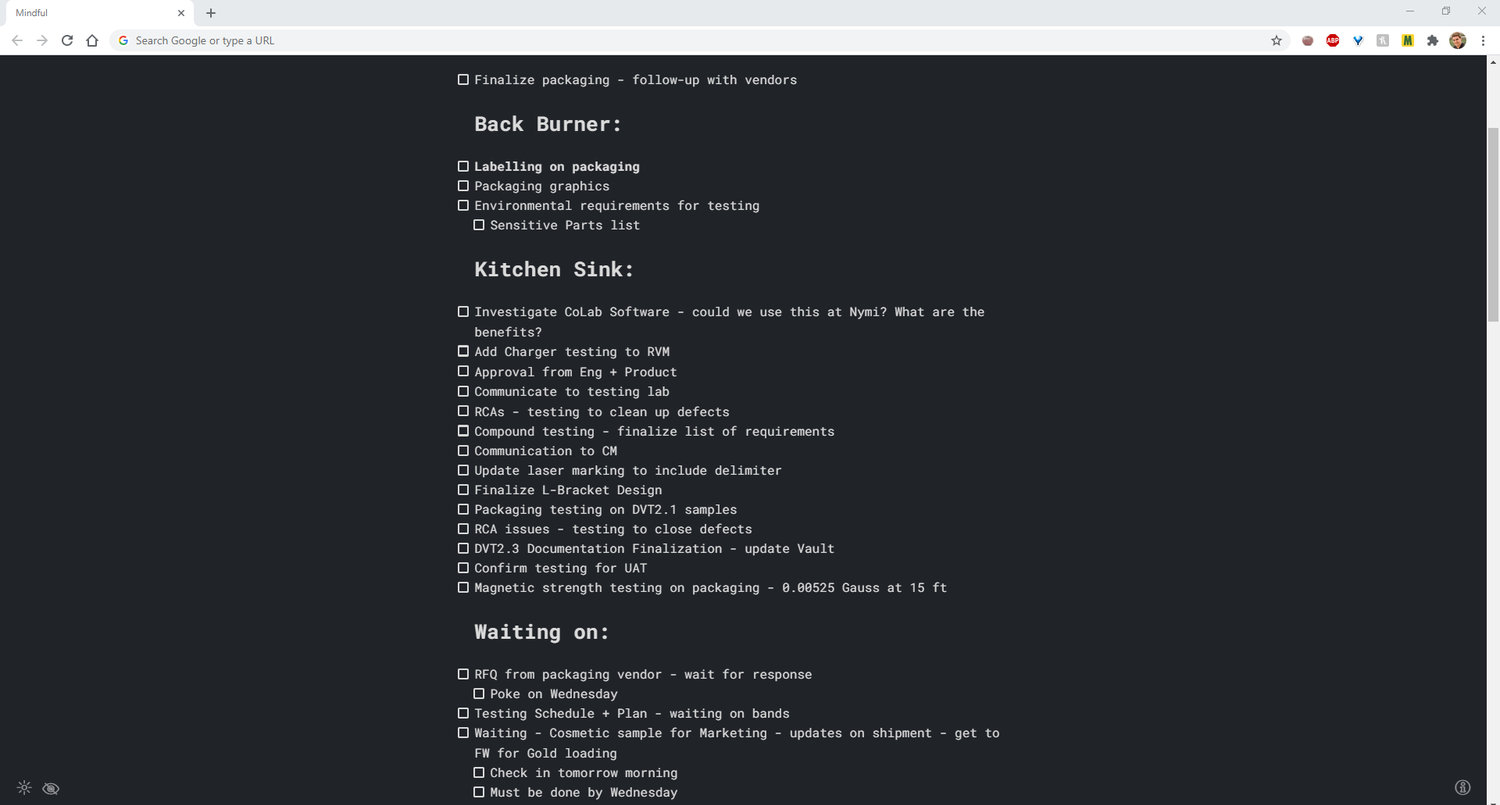

Screenshot of new browser using Mindful Chrome extension and implementing the Kitchen To-Do List.

At the top, I added a small note to remind myself to breathe. A big checklist can induce stress, and this reminder helps me to combat that feeling.

Next I have my Highlight - in this case picking up a shipment and getting some products to people who need them.

After that I have something on the Front Burner - in this case finalizing the packaging I’m working on - which is high priority but does not take precedence over the Highlight. It’s a high priority, but not #1.

Next, my 3 Back Burner tasks, one of which has a sub-task called out. These are items I will get to when I get to them.

Lastly, the Kitchen Sink has a long list of stuff I will do when I have free time.

Screenshot of new browser using Mindful Chrome extension and implementing the next part of the Kitchen To-Do List.

Further down, I have a Waiting On section which items I’m still responsible for, but am ultimately waiting on someone or something else to take the next step. These are meant as reminders, and I have dates associated with some of them.

Screenshot of new browser using Mindful Chrome extension and implementing the final part of the To-Do List: Personal and Daily Routines.

Lastly, I have a section for Personal items and a reminder checklist for Daily Routines.

As you can see in the Personal items section, there are some items I have checked off but not deleted, which is a reminder to myself to follow-up on these before getting rid of them. For example, I went through my clothes and made a pile I want to donate, but have not taken them to the donation bin yet. This item is checked off but not deleted.

Summary / TL;DR

Set a Daily Highlight. This is the most important thing on your list, takes precedence over everything else, and will you feel like you accomplished something at the end of your day.

Set up your To-Do list. I like the Kitchen To-Do list technique: Front Burner (1 item), Back Burner (3 items), Kitchen Sink (everything else), with the added section of Waiting On. Make your system work for you.

Use an app or note-taking system that works. I like the Mindful Chrome extension, but Evernote, Slack, pen and paper, and writing on your forearm are all viable options. Do what works for you.

Make it front and center. Put it in a place you are going to see it often and is easily within reach. When you get that sudden call from an executive or your partner, be ready to take notes.

Keep it simple, stupid. The KISS rule doubly applies here: the more complicated, the harder it will be to implement, and the more stress it will cause you. Simple is best. Don’t over analyze, tweak as you go.

Breathe. You’ve done the hard part: getting a system in place. The next step is to make it work for you and become the magical productivity unicorn you were meant to be. Take a deep breath and remind yourself it’s all going to be okay.

And that’s it! This is the best To-Do System I’ve come up with so far